With the continued increase of human-caused damage to the climate despite COVID-19, researchers are looking towards much-needed measures of mitigation. One strategy that has proven potential involves using the world’s natural landscapes to protect our environment. From wetlands to forests, grasslands and farmlands, there is significant opportunity to store a whole lot of carbon. These storage systems are known as carbon caches.

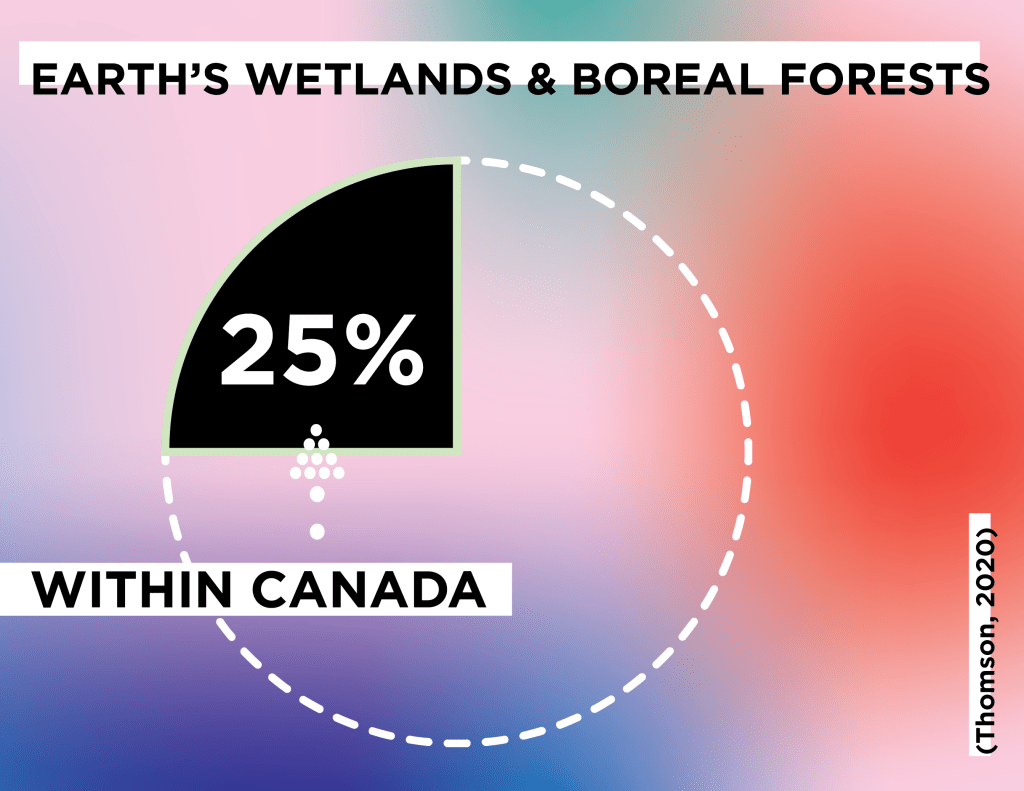

Looking at the data directly, nature-based carbon caches could offer over 33 per cent of emission reductions necessary to stabilize the world’s temperature increase below 2°C by 2030. Recognizing the state of Canada and its geographic diversity, it’s not surprising that it holds a quarter of global wetlands and boreal forests as well as endangered prairie grasslands. Given the introduction to this blog post, it’s also not surprising that alongside all of those resources, Canada has a significant role to play in tackling the current climate emergency.

So, is this an easy fix?

It’s important to note that despite the potential of science, it does not look as though there will be one silver bullet invention to halt the climate crisis. As journalist Jimmy Thomson writes, “No promise to geoengineer the skies or seed the ocean with iron or suck carbon out of the atmosphere has really come to fruition.” Nonetheless, research has found a logical and remarkable strategy. We can save the world’s natural resources by taking efforts to protect and save our natural resources. It sounds strange, but really comes down to the fact that we can use the impressive power of nature to protect our climate.

Looking to Indigenous-led conservation

Before the pandemic, the Nature-Based Climate Solutions Summit was held in Ottawa. During this conference, the federal government set goals around protecting 30 per cent of lands and oceans by 2030, alongside allocating funding to nature-based climate solutions such as planting trees.

Steven Nitah, Dene leader and former Northwest Territories Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA), attended the conference and shared his advice around the concept of land relationship planning. He points out that this is not just about how humans use the land, but about planning our relationship with the land over time. Nitah has experience with that, as chief negotiator role for Łutsel K’e Dene First Nations. In that role, he worked to create Canada’s newest national park, called the Thaidene Nëné National Park Reserve, covering over 26,000 square kilometers of lakes, rivers, wildlife habitats and old-growth boreal forests. The park was created and is operated using Indigenous land management techniques.

Nitah has valuable insights. Our world previously controlled its own climate cycle, and only in the last couple hundred years have humans managed to make drastic impacts to the climate on a global scale. At this point, the natural systems to balance atmospheric carbon still exist in our landscapes, including our forests and oceans.

What does all of this mean?

Climate change is growing more threatening each year. Looking to the scientific data, using nature for carbon storage is much easier while we still have the nature to use. Simply put, protecting pre-existing forests is easier than building new ones. It is 150 per cent more expensive to create artificial wetlands, which are less effective at carbon storage, compared to protecting existing wetlands in the first place. Scientists and researchers recognize this reality, with the United Nations declaring the years 2021 to 2030 as the decade on ecosystem restoration.

These natural carbon storage system have benefits beyond climate mitigation. Carbon caches like Canada’s Boreal Forest offer land purification, soil stabilization, recreational opportunities, water filtration, habitat for wildlife, and flood protection — the list goes on. A restoration-focused future can protect so much of the world’s biodiversity and valuable habitats, while saving lives and mitigating the damage of climate change.

“The places that hold the most carbon are often the places that support the most biodiversity.”

— Ashley Thomson (2020)

What can we do to make things better?

Within Canada, Indigenous people are leading many protection and conservation efforts. The Cree Nation, for example, has protected 15 per cent of their natural territory in northern Quebec, and are aiming to reach 30 per cent. Preserving areas that are not environmentally important, but also culturally significant to Indigenous populations, leads to greater resiliency and opportunities for further protection.

Graham Saul, the executive director of Nature Canada, has outlined the importance of nature-based climate solutions. He notes that the efforts we make to mitigate climate change can have added impacts in restoring our own relationships with the land.

As part of the International Boreal Conservation Campaign, a poll by Pollara Strategic Insights found that “70 per cent of 3,019 respondents across Canada want to see conservation of nature included as part of the economic recovery. The poll also found 72 per cent of respondents believe the government should invest in Indigenous stewardship as part of the economic recovery.”

Through collaboration with Indigenous climate leaders, as well as looking to examples such as the Civilian Conservation Corps, there is so much room for us collectively in the battle against climate change. If you’re interested in learning more, there are a variety of explorative in-depth articles about saving forests, protecting peatlands, and storing carbon in salt marshes at TheNarwhal.ca.

A good post. Thank you 🌍

LikeLike